Análisis de como algunos países del mundo, afectados por la guerra civil o el conflicto armado interno, se han acercado a la justicia.

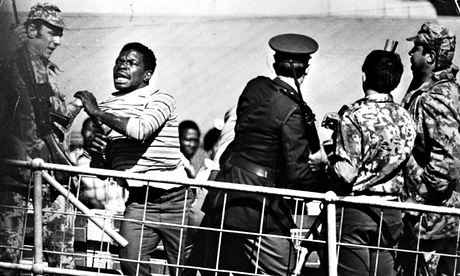

Anti-apartheid protests in Soweto in 1976 in which more than 100 people were killed and more than 1,000 injured. Photograph: Keystone/Getty Images

When Gerry Adams was released without charge last month after questioning over the 1972 killing of Jean McConville, the Sinn Féin president said the case highlighted the need for a victim-led truth and reconciliation process to lay to rest the legacy of the Troubles. Here we examine how other countries that have lived through civil war or internal conflict have approached the issue of transitional justice and reparations, and to what degree they have been successful in underpinning a lasting peace

South Africa

After the feast of liberation came the reckoning. Emerging from decades of racial apartheid, a form of legalised discrimination in which thousands died and millions were marginalised, South Africa's first democratic government set up a truth and reconciliation commission (TRC). Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who chaired it, described it as "an incubation chamber for national healing, reconciliation and forgiveness", and to many around the world it remains the gold standard.

Sitting in the late 1990s, the TRC illuminated horrors committed under white minority rule. Victims gave harrowing testimony of being jailed and tortured, and families described how their loved ones were killed or disappeared. They looked perpetrators in the face as they confessed their crimes, lured by the promise of an amnesty for politically motivated violence. Uniquely, the cathartic hearings were open to the public and broadcast on TV.

"I think it was overwhelmingly successful in what it set out to achieve," said Albie Sachs, a former African National Congress (ANC) activist who lost an arm and eye in a bombing by apartheid agents. "It didn't set out to reconcile everybody in South Africa. That'll only happen when we end up having real equality in, say, work, housing, health and education, and that's taking time.

It had to deal with sources of extreme pain that were being denied, to bring it out into the open. It had to enable people to discover the bodies of members of their families who'd been secretly buried, to get the bones, to give a dignified funeral, to discover the last moments."

The TRC heard confessions from more than 7,000 perpetrators and took about 20,000 statements from victims. It found the ANC's armed struggle was legitimate, but that some acts carried out during that struggle were not. This angered some in the ANC but Sachs, a former constitutional court judge and an architect of South Africa's post-apartheid constitution, said: "It had to involve a degree of acknowledgment by those who'd done terrible things, not only on the side of the regime but also members of the ANC, to which I belonged. We'd done bad things. We had to come clean on that.

"To me, the most important part of the truth commission was not the report, itwas the seeing on television of the tears, the laments, the stories, the acknowledgements. As one political scientist put it, what the truth commission did was convert knowledge into acknowledgment."

Nelson Mandela thanked the TRC for doing a "magnificent job", but acknowledged its imperfections. Some victims felt bitter as they watched self-confessed murderers walk free and did not receive promised compensation. Some believe Mandela and the TRC were too forgiving and that white people continue to reap the rewards of apartheid.

In the Mail & Guardian last month, Tutu lamented how Mandela's successors had left TRC business "scandalously unfinished". He said: "By unfinished business, I refer specifically to the fact that the level of reparation recommended by the commission was not enacted; the proposal of a once-off wealth tax as a mechanism to effect the transfer of resources was ignored, and those who were declined amnesty were not prosecuted.

"Healing is a process. How we deal with the truth after its telling defines the success of the process. And this is where we have fallen tragically short. By choosing not to follow through on the commission's recommendations, government not only compromised the commission's contribution to the process, but the very process itself."

Jesús Muñecas Aguilar, 77, accused of beating Andoni Arrizabalaga in 1969, walked free in April. Photograph: Pierre-Philippe Marcou/AFP

Jesús Muñecas Aguilar, 77, accused of beating Andoni Arrizabalaga in 1969, walked free in April. Photograph: Pierre-Philippe Marcou/AFPSpain

When Andoni Arrizabalaga's family visited him in the police barracks after his arrest in 1969, he had been so brutally beaten that they could barely recognise him. "That's what happens when you refuse to cooperate," they were told.

The former Civil Guard police officer accused of beating him, Jesús Muñecas Aguilar, 77, walked free from a Madrid court in April. "I never even met the man," Muñecas told the judges. They were not interested, however, in the details of whether he had been a torturer. As far as they were concerned, however, the alleged beating took place 45 years ago and so any offence would have lapsed.

Spanish judges' hands are doubly tied when it comes to investigating the thugs who served General Francisco Franco's rightwing dictatorship. Abuses not covered by the statute of limitation are protected by an amnesty law passed two years after Franco's death. Politicians anxious not to place Spain's fragile new democracy under stress, tacitly agreed to sweep the past under the carpet in what became known as the "pact of forgetting".

The pact began to fall apart a decade ago as campaigners started to search for and dig up mass graves, but the 1977 amnesty law means no official has ever been tried for what the lawyer Carlos Slepoy calls brutal and systematic repression. "What we want to do is prove these tortures were part of a wider plan," he said. That would allow cases to be treated as crimes against humanity which, under international human rights law, could not lapse or be covered by an amnesty. About 350 victims, including leftwing activists and former armed Basque separatists such as Arrizabalaga, have joined forces to try to prove the torture was systematic.

Resistance to investigating the crimes of the Franco era is deeply embedded in Spain's judiciary. Baltasar Garzón, the crusading Spanish magistrate famous for pursuing Latin American human rights abusers, was reprimanded by the supreme court for trying to circumvent the amnesty law to bring a case against senior Francoist officials in 2012. He has since been temporarily expelled from the judiciary in a separate case, and this year the conservative government of Mariano Rajoyforced through a law designed to kill off Spanish investigations into human rights abuses in China, Guantánamo and elsewhere.

Garzón's trailblazing has nevertheless proved key in pursuing Franco's torturers, and the process has been taken up by María Servini de Cubríaan investigating magistrate based 6,200 miles away in Buenos Aires. Muñecas was in court last month because Servini had asked for his extradition. Her request followed a precedent set by Garzón set in the Augusto Pinochet case, which saw the ex-dictator arrested in London and his extradition approved by the law lords before the then home secretary, Jack Straw, used his powers to send him home. That case, and others Garzón pursued, established the right of foreign courts to try human rights cases when domestic courts are stopped from doing so.

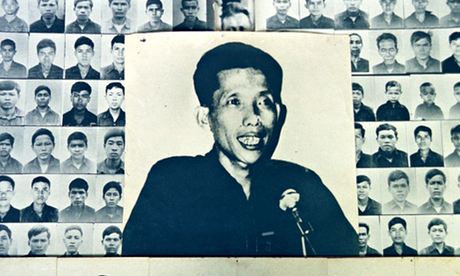

A portrait of Kaing Guek Eav is displayed in the among prisoners at Tuol Sleng prison in Phnom Penh, 1999. Photograph: Ou Neakiry/AP

A portrait of Kaing Guek Eav is displayed in the among prisoners at Tuol Sleng prison in Phnom Penh, 1999. Photograph: Ou Neakiry/AP

Servini's request to extradite Muñecas was rejected in part because the Spanish judges did not accept that the beatings were part of a systematic plan. "If we can change that, there is a chance cases may even be tried in Spain," said Slepoy. The family of Arrizabalaga and those of hundreds morevictims hope that will be the case. If so, they say, those responsible for Francoist repression may also soon find themselves on trial.

Cambodia

It was heralded as the most important trial since the Nazis were confronted at Nuremberg, an opportunity to ask the men who orchestrated the deaths of nearly 2 million Cambodians a simple question: Why?

The extraordinary chambers of the courts of Cambodia (ECCC) began sitting in 2006 and have so far cost more than $200m, but the tribunal has been plagued with charges of corruption, obstruction and interference; and judges and investigators have resigned. It has produced just one verdict in eight years, convicting Kaing Guek Eav, aka Comrade Duch, of crimes against humanity, and sentencing him to life imprisonment. Kaing oversaw the Tuol Sleng prison where an estimated 15,000 Cambodians were tortured and executed.

During the Khmer Rouge's murderous reign from 1975 to 1979, men, women and children were marched out of their schools and homes all over Cambodia and sent to rural work camps under re-education programmes. Many died of disease and starvation. Others were detained in overcrowded centres, tortured and executed as part of a programme to create a communist agrarian utopia. By the time Vietnam liberated the nation, a quarter of the population had been killed.

For many Cambodians, reconciling the past is impossible while former Khmer Rouge cadres still act as government ministers and head the armed forces. The prime minister, Hun Sen, is a former Khmer Rouge commander. Many survivors have tried to forget their childhood by refusing to talk about it, while those who actively search out answers can find themselves harassed, detained and threatened by the state.

It took nearly 10 years from the UN's offer of help in 1997 to establish a hybrid court, manned by Cambodian and international judges and prosecutors. It was hoped that senior Khmer Rouge members would be tried for war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide. Many of the former cadres closest to Hun, however, including the senate president, Chea Sim, and the national assembly chairman, Heng Samrin, have been prevented from testifying, apparently to avoid embarrassing the government.

Such obstructions do not necessarily render the entire process a sham, as some critics have said. "Justice is extremely important," said Youk Chhang, who survived the Khmer Rouge and now heads theDocumentation Centre of Cambodia. "It is the most important thing for a country like Cambodia. Nobody wants to live with the past. The whole point of the tribunal is to move on."

The court's plodding proceedings mean time is running out to deliver sentences and find answers. Of the four senior figures on trial under the current case, 002, one has already died and another has been declared mentally unfit to stand trial. That leaves just Pol Pot's righthand man, Nuon Chea, now 87, and the former head of state, Khieu Samphan, 82. Both are weak and unwell. The ECCC expects case 002 to take another year, and hearings for cases 003 and 004 have been delayed.

Relatives of disappeared political prisoners demand justice at rallies in Santiago, 1985. Photograph: Julio Etchart

Relatives of disappeared political prisoners demand justice at rallies in Santiago, 1985. Photograph: Julio Etchart

For some victims, the trial has thrown up perhaps the most pressing question of all: what constitutes justice?

"Justice is so much more than whether Khieu Samphan or Nuon Chea have lawyers defending them," said Theary Seng, a human rights lawyer who lost both his parents in the genocide. "I and other victims never demanded nor expected perfect justice. What the Khmer Rouge tribunal is producing now is beyond the pale of anything resembling justice. To the contrary, the farce, the deceit, is damaging and is laying the dangerous groundwork for future instability and impunity."

Chile

During the 17 years that Augusto Pinochet ruled Chile, at least 3,000 people were killed or disappeared and 35,000 were tortured, but a semblance of legality survived and kindled a national movement for reconciliation and truth.

Today, dozens of former secret police officers are imprisoned, 350 human rights investigations remain open and the nation is governed by Michelle Bachelet, herself a torture victim. The most recent nomination to the Chilean supreme court is Carlos Cerda, a judge who made his name fighting for victims of human rights abuses. "He was maybe the only one who dared confront the criminal power that was the dictatorship's repression and genocide," said Lorena Pizzaro, who heads a group whose relatives were disappeared.

Pinochet's successor, Patricio Aylwin, created a human rights commission to investigate and quantify the abuse soon after he was elected in 1990. Their mission was to shine a light into the darkest corners of state-sponsored murder. Thousands of cases were validated and formed the basis of a national discussion on how to prevent tit-for-tat vengeance.

Aylwin also set up a secret intelligence squad to capture the underground guerrilla groups that had grown weary of waiting for justice and begun to assassinate former Pinochet aides including the senator and law professor Jaime Guzmán, a law professor, who was shot dead as he left the Catholic University of Chile.

The secret squad was led by Marcelo Schilling, a socialist leader and former bodyguard to Salvador Allende. It was a controversial operation that Schilling today defines as a success. "Today there are no armed groups and the businessmen walk around without bodyguards. Democracy is not in check," he said. "All that was achieved with total respect for individual liberties and human rights."

Clandestine guerrilla groups ridicule Schilling's version, and say he oversaw a brief but illegal dirty war in which rebel leaders were bribed or executed.

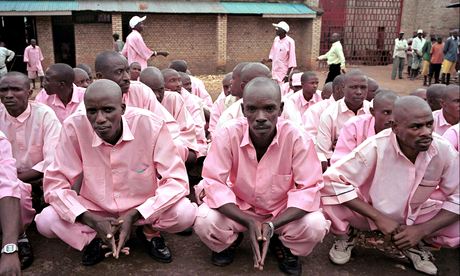

Inmates waiting to be tranfered to a gacaca court session in relation to the 1994 genocide. Photograph: Thomas Lohnes/AFP/Getty Images

Inmates waiting to be tranfered to a gacaca court session in relation to the 1994 genocide. Photograph: Thomas Lohnes/AFP/Getty Images

Few Chileans, however, seemed to have acquired a taste for vengeance. Political violence was minimal in the years after Pinochet. Instead, there was a quest for justice.

The collective amnesty Pinochet had granted was overturned on the basis that if the regime had kidnapped or disappeared citizens but never handed over the bodies, then the cases could be defined as ongoing and so exempt from immunity. This allowed investigators to force testimony from retired officials with knowledge of human rights crimes. Nearly 100 were convicted.

However, attempts to bring Pinochet to justice failed. His title of senator for life shielded him from Chilean justice. The Spanish magistrate Baltazar Garzón indicted him for human rights violations, and he was arrested in London in 1998. The British government released him on medical grounds in 2000 and he returned to Chile, where a constitutional amendment gave him further protection. Pinochet spent his last years surrounded by lawyers, but died a free man at 91 without having been convicted of any crimes.

Rwanda

The scale of the Rwandan genocide, in which 800,000 people were murdered in 100 days, demanded a unique response if there was to be any hope of reconciliation. It came in the form of village courts known asgacaca after the grass on which they were held, a grand experiment in popular justice that ran for a decade with locally elected judges hearing an estimated 1.9 million cases.

Former Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in 2008 in the Hague. Photograph: Serge Ligtenberg/Getty Images

Former Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in 2008 in the Hague. Photograph: Serge Ligtenberg/Getty Images

Trials were held in public, giving survivors the chance to confront alleged perpetrators in full view of their families and neighbours. Defendants faced penalties including life imprisonment and hard labour, but were given shorter sentences in exchange for confessing and were encouraged to seek forgiveness.

"There was a feeling that everyday Rwandans needed to feel involved in the process," said Phil Clark, author of The Gacaca Courts, Post-Genocide Justice and Reconciliation in Rwanda. "It was a way of doing intimate justice for what was a very intimate crime. It was incredibly successful at coming to terms with the very specific crimes committed in communities. There was a lot more clarity about the past. It recognised the role of everyday perpetrators, that the genocide wasn't just committed by the elites in Kigali."

The courts closed in 2012, though according to Clark "the process of reconciliation continues today but informally. Nearly all the perpetrators convicted through gacaca now live alongside survivors. Most communities are peaceful, but people are still working through the issues raised at gacaca. Churches, micro-credit cooperatives and other non-government actors play an important role in continuing to facilitate reconciliation, building on the work done at gacaca. But, generally, people are doing this for themselves."

There were also pragmatic reasons for gacaca. The official judicial system would have been overwhelmed by the caseload. Critics, however, said the courts fell short of international legal standards. According to Human Rights Watch, there were limitations on the ability of the accused to defend themselves effectively; numerous instances of intimidation and corruption of defence witnesses and judges; and flawed decision-making by inadequately trained lay judges. "In addition, gacaca did not deliver on its promises of reparations for genocide survivors. Survivors received no compensation from the state, and little restitution and often overly formulaic apologies from confessed or convicted perpetrators, casting doubt on the sincerity of some of these confessions," Human Rights Watch concluded. "While gacaca may have served as a first step … it did not manage to dispel distrust between many perpetrators and survivors."

Unlike South Africa's truth and reconciliation commission, which dealt with atrocities on all sides, gacaca focused specifically on the genocide against the Tutsis, which meant the accused were almost exclusively Hutu. Fanie du Toit, the executive director of the South African-based Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, said: "There's also a Hutu narrative that's not genocidal. Perpetrators and victims are living together. The question is: is there simmering resentment there? There is no room for expressing that, but that's not to say there won't be in the future."

Bosnia

The question of justice was not completely ignored, but it was set deliberately to one side in the negotiations that led to the Dayton peace accords in November 1995. Parties to the conflict were called on to cooperate with the international criminal tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in The Hague, but there were no sanctions for failure to comply, and the Nato-led peacekeeping force was under no obligation to find indicted war criminals.

For more than 18 months, Nato troops pretended not to see the indictees. They were under instructions only to detain them if they came across them "in the course of their normal duties". Over time, however, it became clear that peace and justice were not mutually exclusive. Civilian and military peacekeepers found the continued impunity of the likes Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladic was poisoning the peace.

A unique chance to break down the ethnic divide that crippled the country may have been lost because of a fear of casualties and mission creep in the pursuit of those known in US military jargon as "persons indicted for war crimes" or PIFWCs.

"Our effectiveness in Bosnia suffered because we did not get aggressive about PIFWCs," said General Montgomery Meigs, a former commander of Nato's stabilisation force. "In the first two years, the Croat and Serb factions were very fragile … Commanders didn't see the PFWICs as a strategic threat and it allowed factions to reassert their control. It was a first-class strategic error."

By summer 1997 the error had been realised, and Nato began arresting suspects. The campaign began with lowly cogs in the machine, camp guards and footsoldiers, while Karadzic and Mladic slipped away to Serbia. Karadzic was caught in 2008, Mladic in 2011.

In the eyes of many Bosnian Muslims, the main victims of the slaughter, justice delayed was justice denied. They were furious that big fish were allowed up to 15 more years of liberty. That feeling of a lack of reckoning has been deepened by recent ICTY acquittals of three figures in Belgrade who played a pivotal role in Serb military operations.

Despite the acquittals, Serbs have continued to see the court as an exercise in one-sided justice. They point to the small number of convictions of defendants charged with crimes against Serbs.

The ICTY trials have laid down a record of the mass murder in Bosnia for future generations and historians, but it has not been accepted as a common narrative among all Bosnia's communities. In the Serb-run half of the country, the school syllabus ends in 1992, and the war is vaguely referred to as a bad time when all sides did bad things. In some of the sites of the worst atrocities against Bosniaks, Serbs have erected monuments to their own fallen soldiers with no mention of the war crimes they committed. In the absence of a shared history, Bosniak, Serb and Croat communities drift further apart.

Colombia

For 30 years, Colombia has been generous with leftwing rebels and rightwing paramilitaries, granting amnesties, pardons and reduced sentences. Demands for justice and reparations for victims were, however, generally ignored in the name of peace.

Today some former rebels are mayors, senators and academics. Dozens of paramilitary commanders, responsible for thousands of murders in the 1990s, are due to leave prison this year at the end of eight-year terms after confessing to their most atrocious crimes.

The current peace talks with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc), the country's oldest and most powerful guerrillas, are different. An offer of impunity is impossible, as the peace process is the first in Colombia negotiated under international criminal court rules. The talks in Havana are widely seen as the best chance to put an end to half a century of conflict that has cost more than 200,000 lives.

"Sweeping heinous crimes under the rug is no longer a viable option for governments and armed groups seeking to strike a deal," said José Miguel Vivanco, the Americas director for Human Rights Watch. "Just as impunity has enabled violence and atrocities for decades in Colombia, sustainable peace won't be possible without holding accountable perpetrators of the worst abuses, such as rape, disappearances and torture."

Officially, the issue of what will happen to demobilised guerrillas charged with crimes is still to be discussed at the negotiating table, but the issues of peace and justice have been at the centre of the national debate since the talks began in October 2012. "There is consensus that the rights of victims have to be respected. The problem is how to do that," said Rodrigo Uprimny, the director of the DeJusticia thinktank.

As Farc and government negotiators began discussions on the issue of victims, the two sides issued a declaration of principles recognising the right to be recognised and to receive reparations, to know the truth and receive guarantees that such atrocities will never happen again.

But Amnesty International pointed out that the document excludes any commitment to bring to justice those who displaced, tortured, killed, abducted, disappeared or raped millions of Colombians over the past five decades. Those details will presumably be part of the final agreement but the formula of transitional justice that will be agreed is still uncertain.

Farc leaders in Havana have made it clear they do not expect to do jail time. "Never has a peace process ended with prison terms for its protagonists, the constructors of peace," said the rebel negotiator Andrés París.

Anticipating a peace deal with the Farc, the government has established an outline of a transitional justice process. It would allow for sentence reduction and alternatives to prison, and let prosecutors focus on those found "most responsible" for atrocities and to concentrate their efforts on the most serious and representative

crimes.

crimes.

Critics say the Colombian state is obliged to investigate and prosecute. Others, however, say trying to pursue every crime would lead to de facto impunity because the justice system could not handle so many cases.

President Juan Manuel Santos, re-elected in June to a second term, denies impunity is on the table, but says demanding full punishment would derail peace. "If you ask a victim today he would lean towards having more justice," said Santos. "If you ask a future victim, he will lean more towards peace."

• This article was amended on Wednesday 25 June 2014 to update the section on Colombia.Fuente The Guardian: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/24/truth-justice-reconciliation-civil-war-conflict?CMP=twt_gu

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario